By Raul J. Palabrica | Philippine Daily Inquirer | July 12, 2015

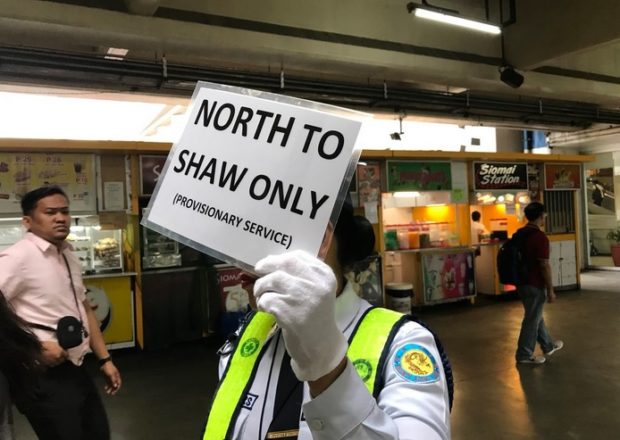

WHO should be held liable for entering into a maintenance contract for Metro Rail Transit 3 (MRT-3) without public bidding?

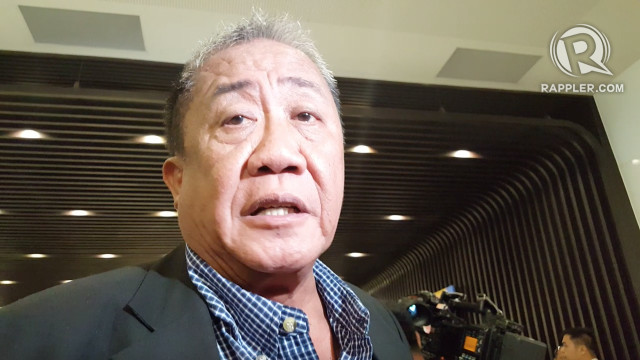

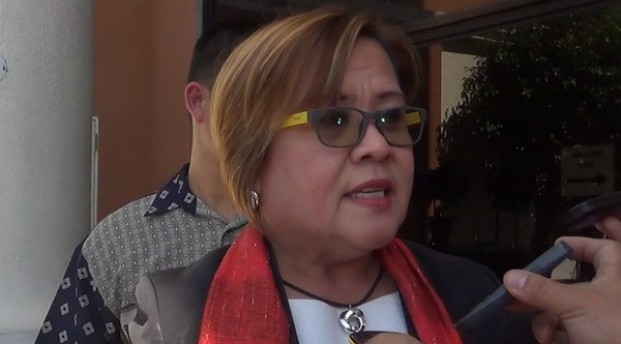

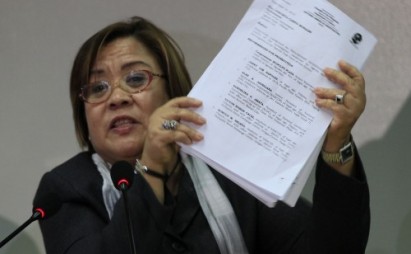

For Ombudsman Conchita Carpio-Morales, it’s former MRT-3 general manager Al Vitangcol, in his capacity as head of the team that negotiated the contract, and the officials of the company that got the contract.

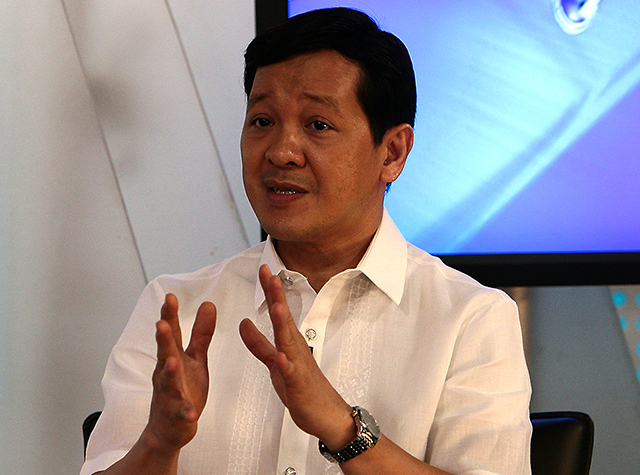

For Sen. Grace Poe, the charge sheet should include Transportation Secretary Joseph Emilio Abaya because he signed the contract.

For Vitangcol, Abaya and Transportation Undersecretary Jose Lotilla should also be held liable because they approved the contract.

In his motion for reconsideration, Vitangcol said that by singling him out for prosecution to the exclusion of Abaya and Lotilla, the Ombudsman engaged in selective justice.

He said “the award was a product of collegial determination” and it would not have been awarded to the company where his uncle-in-law was a stockholder “had it not been for the subsequent approval of Lotilla and Abaya.”

He said the bids and awards committee, of which he was only a member, acted in accordance with the instructions of the Department of Transportation and Communications.

Management

If the same incident happened in a private company and the contract appears to have been entered into in violation of company regulations, all the people involved would be asked by management to explain in writing their side on the matter.

Most probably, members of the negotiating team will claim they acted in the company’s best interests and that they exercised due diligence in recommending whom to award the contract.

The executive who signed the contract might say he acted on the basis of the recommendation of the negotiating team, and that he relied in good faith on their judgment.

He can also say his reliance is reasonable because it is impractical for him to personally examine the covering documents or conduct an ocular inspection of the facilities of the bidding company.

Doing any of those acts would duplicate the work of the negotiating team and would go against the business principle of delegation of duties and responsibilities.

He can further claim that, as manager, he should focus his attention on major policy decisions and let the staff perform the nitty-gritty work needed to assist him in his managerial functions.

Good faith

The same principle of delegation of authority and responsibility applies to government offices.

In a case involving a government auditor accused of negligence, the Supreme Court said “all heads of offices have to rely to a reasonable extent on their subordinates and on the good faith of those who prepare bids, purchase supplies, or enter into negotiations.

“Any executive head of even small government agencies or commissions can attest to the volume of papers that must be signed. There are hundreds of documents, letters, memoranda, vouchers, and supporting papers that routinely pass through his hands. The number in bigger offices or departments is even more appalling.”

Those who regularly transact business at government offices can attest to the volume of paper work that has to be accomplished and submitted to obtain government documents.

After going through the bureaucratic maze, the final signing authority usually checks if the required supporting papers are attached or the officials below him have signed or affixed their initials at the proper places.

When assured that the procedures have been complied with and there is no reason to doubt the integrity of the people who recommended the signing of the documents, the official concerned signs them.

Accountability

This is not meant to be a brief for Abaya and Lotilla on the MRT-3 contract now subject of a complaint by the Ombudsman.

If the two DOTC officials were in the private sector, the controversy brought about by the awarding of the contract would have put them in hot water.

But fair is fair. Although command responsibility has a nice ring when accountability in government is talked about, there are limits to its application.

The heads of government offices cannot be faulted for delegating to their subordinates certain duties and responsibilities that the latter can, within the limits of their competence, ably perform.

Micro management has long been proven to be an inefficient way of running a business, more so a government office that supervises several facets of human activities.

Unless a government executive is “superman” incarnate, there are physical limits to his ability to perform his mandate efficiently within the time frames required by his position.

By sheer force of necessity and for reasons of practicality, he will have to seek assistance or guidance from his staff in the accomplishment of his duties and responsibilities.

To require him to personally perform, or double-check everything that his subordinates do, to ensure their compliance with existing regulations would be sheer idiocy.

The mere fact that Abaya’s, or any government official’s, signature appears in a questioned contract or document is not sufficient to hold him liable for any perceived violation of government rules.

To borrow the words of the tribunal in the case earlier cited, “there should be other grounds than the mere signature or approval appearing on a voucher to sustain a conspiracy charge and conviction.”

The burden of proof is on Vitangcol to show that Abaya or Lotilla committed acts other than signing or reviewing the contract in question that made it susceptible to scrutiny for violation of the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act.

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook