By Jarius Bondoc | The Philippine Star | April 11, 2014

It’s been a year since Czech Ambassador Josef Rychtar reported the misdeed to Transportation Sec. Joseph Abaya. Allegedly in July 2012 Al Vitangcol, head of the Metro Rail Transit-3, had tried to extort $30 million from Czech train maker Inekon. Since then news sensations have implicated presidential kin and party mates. Too, Rychtar has detailed the scam in a

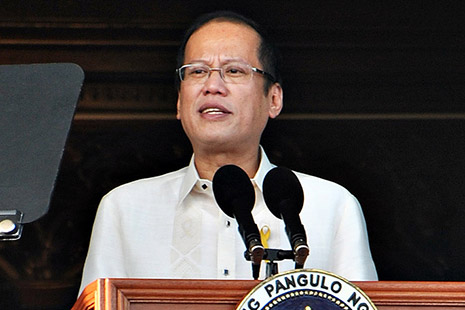

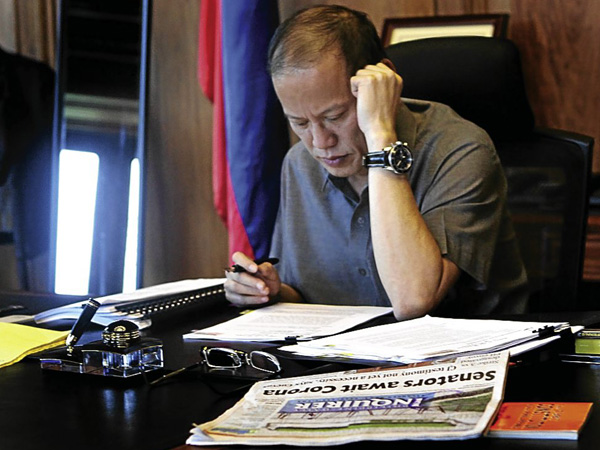

much-publicized letter to President Noynoy Aquino. But apart from a closed-door internal inquiry that ended in Vitangcol’s quick return, there has been no closure. Suspicions are rife of a Malacañang cover-up.

To be sure, no proof of fraud has been forwarded against P-Noy’s elder sister Ballsy Aquino and spouse Eldon Cruz. Just that, on Rychtar’s invitation, the couple had travelled to Prague where businessmen feted them. Ballsy has confirmed to the press that 2011 pilgrimage to the Shrine of the Child Jesus.

Curiously about that same time, though, P-Noy and Ballsy’s first cousin Jorge Aquino Licauco was consulting for Inekon. Its maintenance contract with Sumitomo Corp. about to expire, the transportation office then was preparing to bid out the renewal, along with resupply of new trams. Reportedly Licauco and Inekon’s Philippine agent Yorgos Psinakis met with then-Transport Sec. Mar Roxas about possibly taking on both deals. After all, Inekon had acquired the original Czech manufacturer in 1994 of MRT-3’s trams.

There is no confirmation of the meeting, or account of the outcome. But one newspaper quoted a controversial letter from Licauco to Roxas’ Undersecretary Rene Limcaoco. In it he sought a revision of the planned supply-maintenance contracts to include refurbishing of the entire MRT-3 fleet of locomotives and coaches. Also quoted was a follow-up letter from Psinakis to Limcaoco. The latter is one of three undersecretaries in charge of multibillion-peso biddings for railways, airports, seaports, and land vehicle registration and platemaking.

Reports of those 2011 letters came out only in July 2013, right after Rychtar’s allegation of Vitangcol’s $30-million caper. Murmurs then were that the linking of the Cruzes, Licauco, and Psinakis was only to divert attention from the extortion attempt.

Still, the government swiftly should have investigated. For, the Constitution forbids from government contracting relatives up to the fourth degree (cousins) of the President, VP, Senate President, House Speaker, and Supreme Court Chief Justice. The only exception is if the relative has been in the contracted line of business or profession five years prior.

Opinion

Had it stepped in, the NBI could have verified if the letters were true, if Licauco has been in railways since 2006, and if the Cruzes had any dealing with Inekon. It would have helped had Licauco himself surfaced. Helpful too had Roxas and Limcaoco confronted the issue. But the job fell on Presidential Spokesman Edwin Lacierda to belie it all.

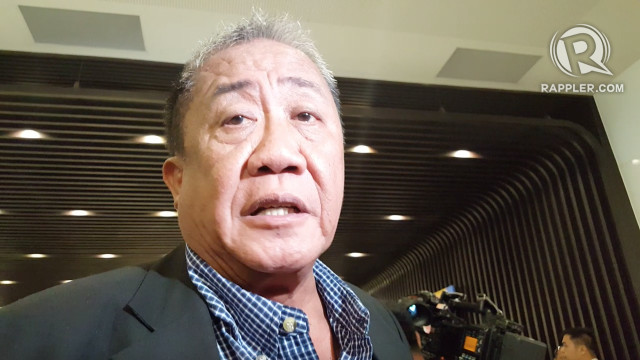

Abaya, who had taken over Roxas’ post by the time scandal broke, for his part tackled the other half of the issue: the $30-million extraction. Citing no reason, he kept repeating that Rychtar was incredible. Lacierda subsequently picked up the anti-Rychtar line. Their name-calling only heightened suspicions of cover-up.

A political angle surfaced. Roxas is president of P-Noy’s Liberal Party. Abaya and Lacierda are high LP officers. Jorge Aquino Licauco appears in Comelec records as contributing P4 million to the successful 2013 LP senatorial campaign of another first cousin, Bam Aquino. Multi-titled Vitangcol and Limcaoco, Roxas’ appointees to the transport department, supposedly helped in P-Noy’s 2010 presidential run. So did one Wilson de Vera, an LP member whom Rychtar alleged actually had asked for the $30 million in behalf of Vitangcol. Was the cover-up an LP activity? (Limcaoco incidentally is facing at least four cases of graft before the Ombudsman in relation to his department’s biddings.)

More incidents fuelled the suspicions. Like, when the NBI finally decided to investigate, it focused only on the Vitangcol angle and avoided Licauco. Even that probe has been inconclusive. The agency had promised a report by last November. Five months on, all it has said is that it couldn’t proceed for lack of a formal complaint. It was like saying it couldn’t look into an entire family’s massacre because there’s no one left crying for justice.

Actually there was a complainant — no less than Inekon chairman Josef Husek. Late as his affidavit came, only in Jan. 2014, the NBI nonetheless has not taken it on. Rychtar’s statement, although in his embassy’s official stationery, was unsigned. But it too should have been a takeoff point, because officially submitted to Malacañang and the Dept. of Foreign Affairs.

Another suspicion rouser was a recent press leak from the House of Reps committee on good government, which belatedly has joined in. Supposedly, Rychtar’s unsigned narrative was worthless, an unidentified member said. And while Hušek’s was signed, it supposedly was not notarized, thus also useless, the source added.

That again was a distortion. Husek’s affidavit has a covering official Acknowledgment — a notarial affirmation, signed by Philippine consul to Prague Juan Dayang Jr. And even if Rychtar’s paper was unsigned, the House committee has initiated past probes on less documentation.

To Vitangcol’s advantage, neither Rychtar nor Husek swore that he directly asked for the $30 million during post-dinner in July 2012. They both stated, however, that he demanded Inekon’s investment in his family-dominated company that would front for the Czechs.

Vitangcol and de Vera both denied having ever dined with the Czechs to discuss any bribe. Still, there were verifiable info bits from Rychtar and Husek’s statements. Like, was it true that when the talks with Inekon collapsed with Inekon’s rejection of the $30-million demand, Vitangcol awarded a temporary MRT-3 maintenance contract to a firm that included de Vera? Probers gingerly have skirted that angle.

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook