By Raul Dancel | The Strait Times | August 8, 2015

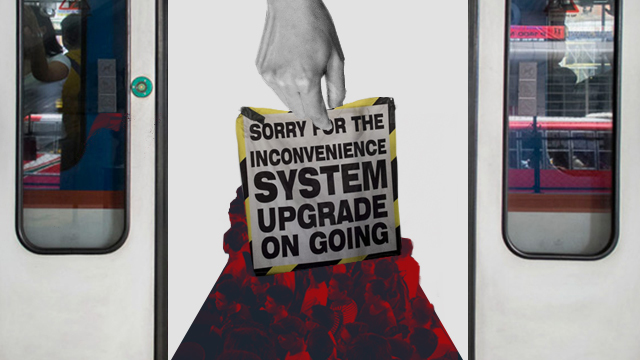

Mired by frequent breakdowns and accidents, the ageing and badly maintained rail system strains to cater to a rapidly ballooning population. A congressional probe finds problems are due to a flawed public-private partnership.

MANILA • Ms Emmie Ballado, 42, an accountant at a small logistics firm, used to take the metro rail system - known to all as the "MRT" - to get to her office in Makati, the capital's prime business district, from her home 16km away.

"It was not convenient. The trains and stations could be scruffy. But it was quick and it was cheap. It got me to the office in about an hour," she said. Ideally, it should take her only 40 minutes on clear roads by car.

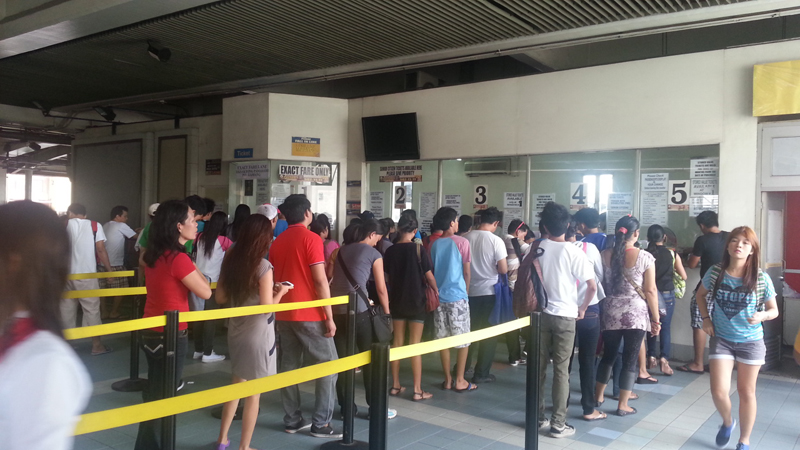

About six months ago, however, she stopped taking the MRT. She was fed up with queueing for at least an hour just to get on a train.

The long lines began appearing two years ago.

There used to be two dozen trains, and a train was at the platform every five minutes, including during rush hour. However in 2012, the trains began breaking down.

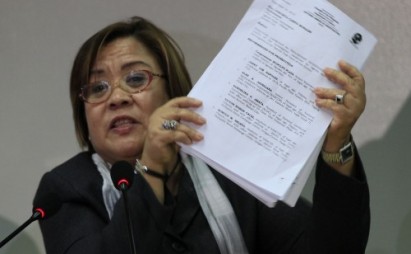

Manila's metro rail system was designed to carry 350,000 passengers daily but is now straining to cope with 600,000 commuters. Yet, the system has not been upgraded to raise its capacity. It has also never been overhauled and maintenance has dipped far below acceptable standards. Train speed is down to 40kmh from 65kmh because of cracks and gaps in the rails. ST PHOTO: RAUL DANCEL

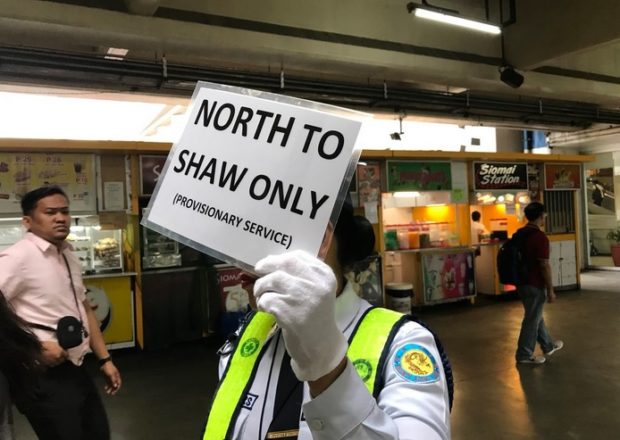

Now, on good days, 14 trains will be running. That means waiting on the platform for 10 to 15 minutes. Sometimes, the wait can last 35 minutes.

There have been days when just eight trains were running. On those days, the head of the queue would be at one station and its tail at the next one 3km away.

There is also the shoving and groping, said Ms Ballado, a woman barely taller than five feet.

"I take the bus now. It takes me two hours to get to the office, but at least I can sit down and take a nap. There's even free Wi-Fi if you're lucky," she said.

The MRT is part of an urban rail system that began with the Manila Light Rail Transit System - the LRT, a north-south line that snakes through the western section of metropolitan Manila, a 640 sq km urban sprawl home to over 14 million.

When it started its service in 1984, the LRT was the crown jewel of the Philippines' public transport system. It was the first mass rapid system in South-east Asia. (Singapore would not have anything like it till three years later.)

Each day, unfettered by road traffic at 8m above the ground, it moved over 300,000 commuters with mechanical regularity across a city that in 1984 was convulsing.

It was a time when the dictatorial regime of Ferdinand Marcos was close to its collapse in 1986 and the city was in chaos. But not the LRT, which ran like clockwork.

I rode the LRT to school, and what I remember most was how different it felt to be moving high above the grime and disorder of the city's streets.

Some 15 years later, in 1999, a new north-south line was added: the MRT, with two of its 13 stations underground.

The MRT cuts through the centre of the city, tracing nearly the entire length of the 23.8km Edsa highway. The 12-lane Edsa is the backbone of the city's labyrinthine network of roads. It is also the most congested.

The MRT was meant to ease traffic along Edsa. With 24 trains, it was designed to carry roughly 350,000 passengers a day.

A new east-west line of the LRT began service in 2004, with a passenger load of 150,000.

But with 14 million now working and living in Metro Manila, up from 12 million in 2000, the number of commuters taking the MRT has nearly doubled to 600,000 - and the line is showing its age.

Though it was carrying more than its specified capacity of 350,000 a day by 2006, the MRT was not upgraded to raise capacity. It has never been overhauled and maintenance has dipped far below acceptable standards.

Nowadays, 14 trains will be on the tracks on good days. On any given day, two to three trains are being repaired. Others are in the depot, waiting for spare parts.

Train speed is down to 40kmh from 65kmh because of cracks and gaps in the rails. Sensors and safety indicators fail regularly.

The result has been misery for hundreds of thousands of commuters who rely on the MRT to get around the city.

There is not a week that passes without news of trains stalling, sometimes for two hours, or breaking down, running with doors open, or running into one another, or going off the rails, or running with leaking roofs on rainy days.

In August last year, 38 passengers were injured when a train ran past the last station at the southern end of the MRT and rammed through a barrier. That same month, MRT operations were halted for half a day because of a communications system breakdown.

Even in the stations, accidents happen. In January this year, 26 people were hurt when an escalator came to a dead stop without warning. Just last month, hundreds of passengers had to walk on rails when their train stalled in between stations.

A study by the Advocates of Science and Technology for the People showed the MRT is "five times more deadly" than those in other countries, with 3.48 injuries recorded for every 100 million passenger-miles.

What is emerging from a congressional probe into the MRT's problems is a flawed public-private partnership that is now in the process of being decoupled.

"The main or root problem seems to be legal and not at all technical. The technical problems experienced are manifestations of a contract that is a textbook case for how not to do a PPP (public-private partnership) programme," said Mr Jose Regin Regidor, a research fellow at the University of the Philippines' National Centre for Transportation Studies.

The MRT is a build-lease-transfer project, built by a consortium of big property developers. The government, through the transport ministry, operates the line, assuring the investors a 15 per cent return on their investments through a 25-year lease - or about US$2.4 billion (S$3.3 billion).

Things started to fall apart when the government decided to start withholding payments and the line's maintenance contractor, Japan's Sumitomo, was replaced in 2012 by an under-capitalised local firm, according to testimonies from investors to a congressional committee.

After 2012, the major breakdowns increased in frequency to three a month, according to the investors.

To the government, however, it had been paying enough: US$779 million from 2000 to 2013.

It insists that the private investors should have ploughed some of that money back to upgrading the MRT by buying new trains and overhauling the entire line as early as 2008. Instead, they let the system deteriorate.

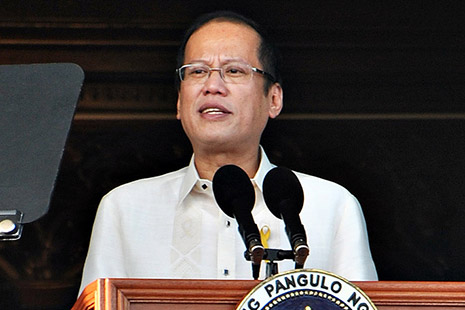

The solution of President Benigno Aquino's government now is to buy out the investors to the tune of 54 billion pesos (S$1.6 billion), which the latter complain is too little.

A Singapore arbitration court is weighing whether the Philippine government can prematurely end its 25-year deal with the consortium.

The investors, meanwhile, are pressing for payments they say the government still owes. They have also filed cases challenging the government moves that they say encroach on their right as owner of the MRT's assets.

The lawsuits will likely outlast Mr Aquino, who will step down as president next year.

By then, with a new leader coming into office, the government's bid to take over the MRT will be up in the air, and with it the line's future.

As for commuters like Ms Ballado, they just want the trains to run on time.

"I hope they can fix it soon. I'll go back in a heartbeat, if only they can stop making me wait," she said.

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook