By Lorenz S. Marasigan | Business Mirror | October 26, 2015

First of three parts

The key to effectively ferry vast numbers of people from one place to another is through mass-transit systems, such as railways. In Asia, the Philippines is proud to have been the first country to have developed such a light-rail transit system in the early 1980s. Its neighbors soon followed its footsteps, and started their own journey into building massive train lines to improve mobility and lessen traffic congestion.

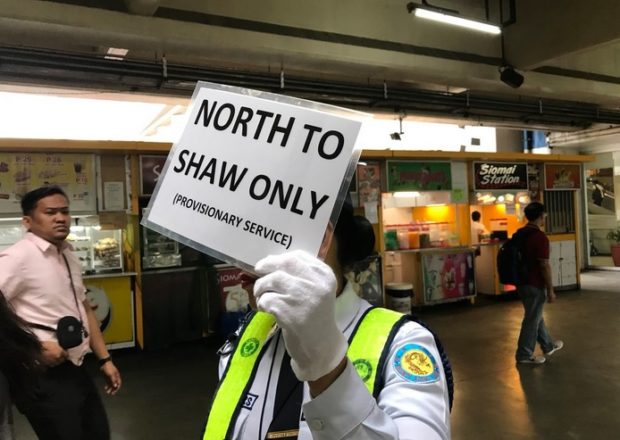

But more than three decades into the inauguration of the first overhead train system in the continent, the Philippines now lags behind its Asian peers with only four working train systems—a heavy rail, two light rails and a commuter line.

Experts and business leaders agree that the government failed to keep up with the times. Underspending, underinvestment and under-the-table deals were tagged as culprits behind the deterioration of the rail sector in the Philippines.

Jose Regin F. Regidor, a transportation expert, lamented the “lousy service” provided by local railways systems.

“The overall state of railways in the Philippines is poor, since we have rail only in Luzon and much of it is in Metro Manila. The Philippine National Railways is still in a sorry state despite efforts within the agency and, so far, it has gotten only little support from the national government, especially from the transport department,” Regidor said.

Regidor, a research fellow at the University of the Philippines-Diliman National Center for Transportation Studies, noted that there have been proposals in Cebu and Davao for urban rail lines, and then there were the proposals to revive Panay Railways and construct Mindanao Railways.

“But, these all have not progressed since the last administration and has gotten little support from the present,” he said.

‘Worst in Asean’

Businessmen echoed the pundit’s observation, frowning at how the government had failed to improve the train systems despite having the money and time to do so.

“Philippine rail system has been left behind by the rest of Asia despite us, historically, having pioneered the light-rail transit in the region. While our neighbors followed our lead, they continued with their programs and ours was left to stagnate, resulting in the deteriorated state of rail today,” Makati Business Club (MBC) Executive Director Peter Angelo B. Perfecto lamented.

In terms of connectivity among different cities, the Philippines is considered as one of the worst not only in Asia, but in the world.

“Intercity is probably the worst in the world; of four Asean capitals with light rail lines— Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, Manila and Singapore—Manila is the slowest to expand and has the poorest maintenance and most overcrowding,” American Chamber of Commerce Senior Advisor John D. Forbes observed.

Filipinos living in the capital are the patrons of the train lines; after all, these mass- transit systems still are the fastest means to go from one part of the city to another.

“The train systems are in bad shape and are in need of upgrades and expansions with urgency,” European Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines (ECCP) External Vice President Henry J. Schumacher noted.

The worst of them all, however, is the “middle child,” the 16-year-old Metrostar Line, more commonly known to the masses as the MRT.

‘Inappropriate’

Manila gave birth to the 17-kilometer mass-transit system in 1999—almost a decade after it was first conceived—with the primary purpose of decongesting the capital’s main artery, the iconic Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (Edsa).

The build-lease-transfer contract was awarded to Metro Rail Transit Corp. (MRTC) two decades ago, when it acquired the company’s original contractor due to its botched agreement with the government.

The 25-year contract essentially provides that the private partner builds the line, the government leases the transport system, and the infrastructure will be transferred to the state at the end of the concession period.

When it was built, observers, at first, thought it was a flop, as its average daily ridership only hit the 40,000-passenger mark. Despite this, the private company that built the train system still insisted on major expansion programs to prevent congestion in the railway line.

The government, however, refused, saying that the train system must first hit the 350,000-passenger mark before it does anything as drastic as an expansion of the line. It hit its rated capacity in four year’s time, but still, the government failed to approve proposals to add capacity to the train system.

As the years went by and the Philippine economy grew faster and faster, the train line’s passengers increased until it hit its crush load, which in layman’s term, is it’s maximum capacity. Still, the government failed to hear the cries of both the consumers and the private partner for modernization.

This led to worse situations along Edsa, as the train line snakes through the middle of the thoroughfare, eating up at least three lanes in the process.

“We now know that a light rail system along Edsa was not appropriate, despite studies back in the 1990s that purportedly supported this. We should have built a heavy rail system along this corridor together with other rail lines proposed in the past that could have formed a good network of transit

lines,” Regidor said. But it seems that it is too late to lament over this fact, and the government is now moving toward the improvement of the line, or so its officials claim.

‘There’s still time’

Aside from procuring P9.7 billion worth of improvement projects, the government is also moving toward the acquisition of the train line to end its obligations to the private partner and essentially improve the hellish ride that commuters have to face on a daily basis.

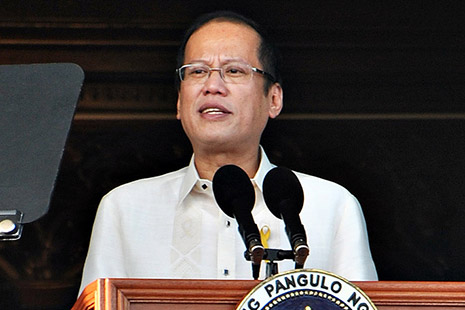

The takeover is enshrined in Executive

Order 126 that was issued by President Aquino in February 2013. The order stipulates that the Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC) and the Department of Finance (DOF) must execute an equity value buyout of the private company that owns the MRT to free the government from paying billions of pesos in equity rental payments (ERPs) to MRTC per year.

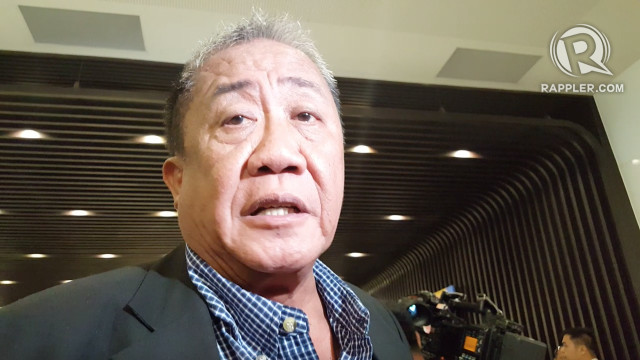

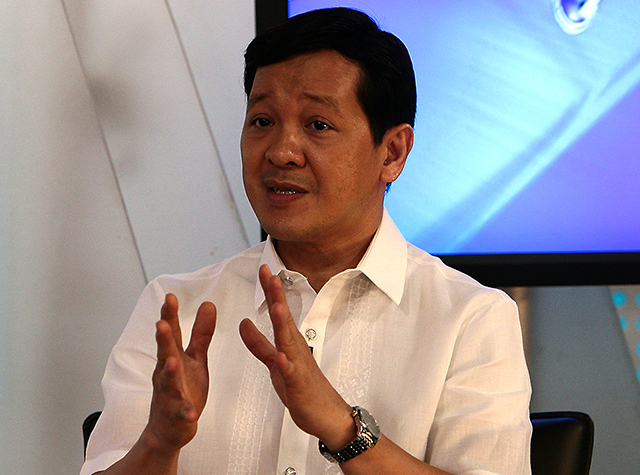

Transportation Secretary Joseph Emilio A. Abaya said the takeover will be instrumental to the modernization of the railway system that ferries more than 540,000 passengers daily.

Before the government can actually buy the private partner out, several steps must be undertaken to ensure that the takeover will be smooth sailing and is within the bounds of international laws.

To fully take over the line, the government must purchase all the shares and the bonds in the railway company. Another requirement of the buyout deal is for the government and the private partner to strike up a compromise deal to end the ongoing arbitration case in Singapore that was lodged against the state in 2008 due to its failure, as the operator of the line, to pay billions of ERPs to the owner of the rail system.

But more than two years into the issuance of the President’s order, the DOF and DOTC have not moved an inch toward the implementation of a buyout. They encountered a number of roadblocks in the not-so-distant past—including a thumbing down of the takeover’s budget by lawmakers—that prevented them from moving forward with the transaction.

The government agencies are trying to get back on their feet and find “creative” ways on how to execute the buyout.

With only a few months left before the President bows out from office in June 2016, the transport chief expressed optimism that his camp can execute the transaction within the term of Mr. Aquino.

“We are keen on pursuing the buyout of MRT 3 from the private-sector owner,” Abaya said. “I think there’s still time.”

But the chairman of the majority shareholder in the private company that owns the train line just laughed the idea off.

‘Nonsense’

MRT Holdings II Inc. (MRTH-II) Chairman Robert John L. Sobrepeña said that he is “amazed” at the persistence of the government—particularly Abaya—in undertaking the multibillion-peso takeover.

“I’m amazed that Abaya is still pursuing the so called buyout when he has failed to do this over the last several years. The reason he has failed, and will fail again, is that it just doesn’t make sense to spend P54 billion to buy the MRT bonds, which are already owned by the government through the Development Bank of the Philippines [DBP] and Land Bank [LandBank] of the Philippines,” he said.

The two government banks together hold roughly 80-percent economic interest in the MRTC by virtue of the bonds they purchased in 2009. “In short, they are spending P54 billion to buy something which they already own, so that they can control MRTC, which they already have complete control of via the DBP-Landbank nominees in the board,” Sobrepeña said. LandBank National Director Tomas T. de Leon Jr. currently sits as the chairman of MRTC.

“The worst is to spend all that money

without a single peso going to much needed rehab and repair of the MRT 3,” the

businessman said.

But for the transport chief, a close friend of President Aquino, the government is better left with the complete ownership of public utility instead of allowing the private sector own the facility.

He cited, for example, the current structure of the LRT Line 1 and the Mactan-Cebu International Airport, both of which are currently being managed and maintained by private proponents, but are still owned by the state. “Managing the train system is really best left to private sector, then the government is regulator,” Abaya said. “Leaving the operations and maintenance to the private sector is the right solution for us.” To be continued

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook