By Lorenz S. Marasigan | Business Mirror | October 26, 2015

Second of three parts

DESPITE their opposition to the buyout deal that the government wants to execute, the majority shareholders of Metro Rail Transit Corp. (MRTC) are still open to a takeover, provided state officials will stop playing around and start properly talking with the real stakeholders.

MRT Holdings II Inc. (MRTH-II) Chairman Robert John L. Sobrepeña said his camp is willing to sell their shares at the right price, which the government earlier set at around P53.9 billion.

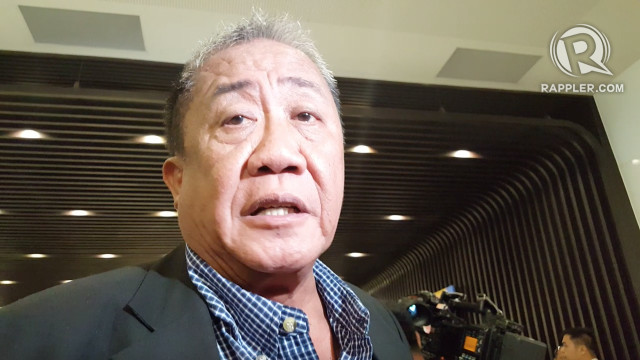

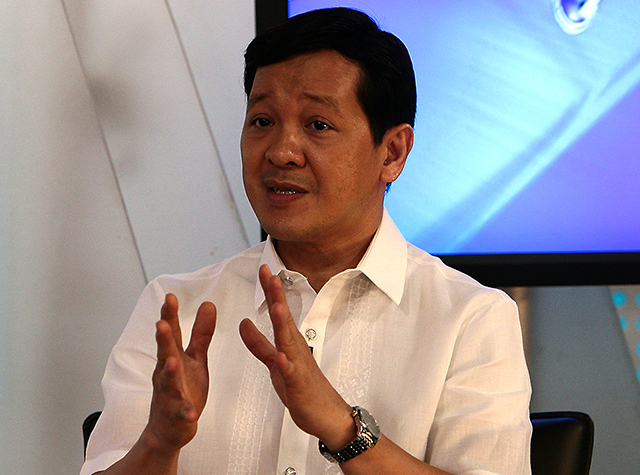

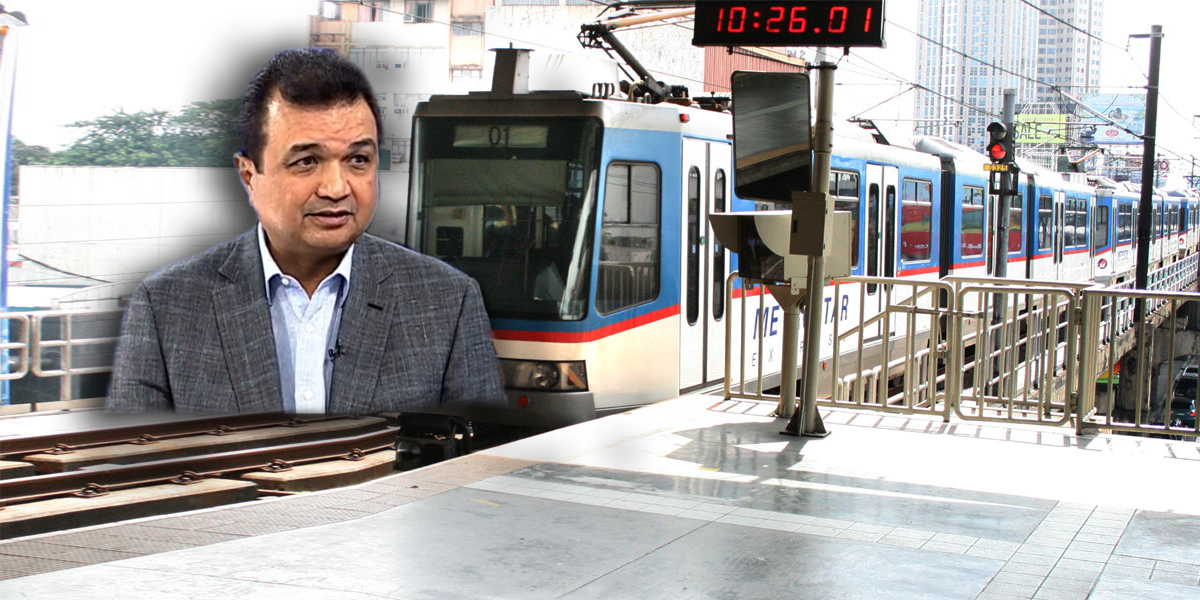

Transportation Secretary Joseph Emilio A. Abaya, however, disputed that the amount has “gone down” due to the government’s payment of the so-called equity rental to the parent company of the train line, the MRTC.

“In the past, we were looking at shelling out P54 billion, a computation that was made a few years ago,” he said. “But we continued to pay the equity rental payments, so the amount has been lowered. It could be less than P50 billion. The last I heard is that the amount is in the high 40s [P40 billion].”

Sobrepeña begged to disagree, saying that the previous computation was only enough to fund the bonds held by the Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP) and the Land Bank of the Philippines (LandBank).

According to the businessman, the price tag for the acquisition of the equity alone will only amount to “less than P25 billion,” given the years left in the concession period.

But a quick check on the web site of the train system showed that the complete takeover of the rail line will amount to more than double the amount that the Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC) announced to the media. The outlay should be around P112 billion, the Web page noted, explaining the movement of prices due to inflation.

“We, the private-sector owners of the MRT 3 system, are willing to sell if the government is, willing to buy us out. But the reality is through all these years of the DOTC saying they want to buy us out, we have not received one single offer or proposal from anyone from the department or Abaya to buy us out,” Sobrepeña lamented.

This is particularly true, as the transport chief admitted that his camp is only talking to the officials of MRTC— mainly composed of the nominees from the government financial institutions (GFIs)— as the party to the buyout deal only involves the aforesaid stakeholders.

“When Abaya says he will talk to MRTC, he means the government nominees who sit in the Board. Those GFI nominees in the MRTC Board are not authorized to negotiate a sell due to conflict of interest,” the businessman explained.

“There is no way that the DOTC can execute a buyout without the consent of the owners, namely MRT Holdings Inc., which is owned by the private sector whom they have not even talked to about a buyout today nor all the years passed,” he quickly added.

Executing 101: Budget

Despite this key hurdle, the transport chief is hopeful that the transaction will be smoother than planned. Funding will be a primary issue to this deal, but Abaya said his camp will push lawmakers to allot the outlays needed to execute the takeover.

“The money will come from the national budget. It is in the unprogrammed fund. We are also convincing Congress to make sure that it is also in the 2016 budget, so that the budget doesn’t become an issue,” he said.

“Even though we get to agree, but we are left without a budget, then something vital isn’t there to execute. We have to make sure that all things are in place.”

His optimism comes a year after Congress decided to scrap the programmed budget for the buyout last year, as lawmakers deemed it unnecessary to pass money from one government office to another.

While the transport chief is bullish that his office will soon receive the needed capital to execute the takeover deal, his main concern now is to convince the Department of Finance (DOF) and the state-owned lending institutions that the takeover is logical.

“The real challenge now is really talking with the GFIs and talking with the DOF because they might take a loss in execution of the buyout,” he said. “The biggest issue here is taking a loss.”

In light of this, the legal team of the transport agency handling the deal will sit down with its peers from the finance department to flesh out the details of the buyout.

“We will discuss to them as to how to execute the equity-value buyout. This is important to them because from our end, we believe that we should only pay for the formulaic equation—the value that we see as fit— for the preferred shares. It is important that they are on board and are also kept cool,” the Cabinet official said. A schedule for a meeting among the financial institutions and the departments has been set within the month, albeit indefinitely.

“What is important is to sit down with the DOF, DBP and LandBank and we’re going to schedule that, say within the month. I have given instructions to our legal team for the meeting,” he said. “We’ve done preliminary work. Our legal team has sat down with the GFIs, and feedback is they are now comfortable with the suggestion. So, what’s important is we come face to face and everyone is comfortable with the track to take.”

During the said meeting, officials that will handle the buyout should come out with a concrete plan on how to move forward with the said transaction.

“I think there will be a concrete plan,” Abaya said. “It is important that we make these things clear—on paper, in concept, and everybody signs.”

Midnight deal

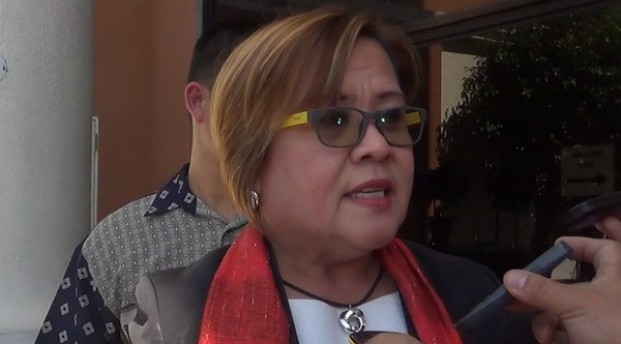

Striking a deal at this point, however, will be deemed by many as an irregularity, especially since 2016 is an election year, and Abaya currently sits as the chairman of the ruling Liberal Party.

“Given the remaining months of the current administration, I think many will look at a deal this late to be somewhat like a midnight deal,” Jose Regin F. Regidor, a transportation expert, said. “It is uncertain at this point how the 2016 presidential elections will go and if the buyout is something that the next administration and transport officials wouldn’t want to inherit despite its inevitability, I can only speculate.”

But for the transport chief, executing the buyout today will spare the next administration from the headaches of paying up billions of rental payments, dealing with the private-sector owner and effectively modernizing the train system without any opposition from another party.

“I’m really hoping to execute this deal because I don’t want the guys who will replace us to experience what we have experienced in this transaction. If I do this, it solves a lot of headache for those who will replace us,” Abaya said.

He did not discount the fact that the private partner will oppose the buyout deal. But the government’s camp is ready to face these challenges that could go as far as going through the courts.

“Those who don’t want this can take us to court and that is also going to be challenging, because it is done elsewhere,” he said, referring to the arbitration panel in Singapore. “That is the theater where we will execute all of these.”

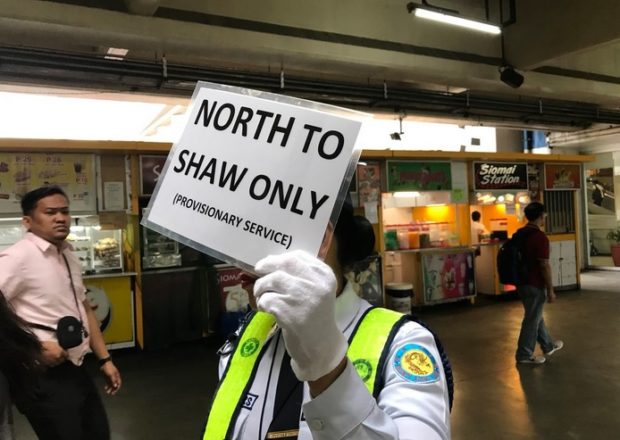

Nonetheless, his team will be up for the challenge of battling any opposition in court to save the government and the commuters from the horrors of the MRT.

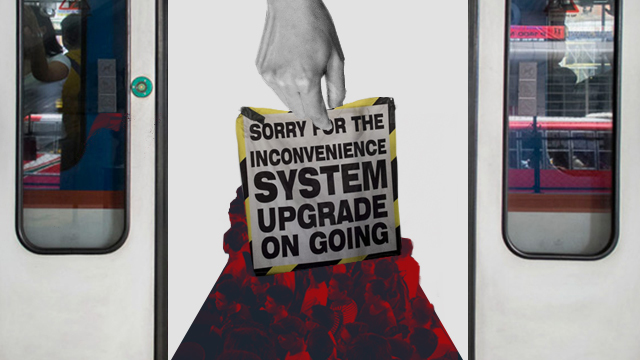

Set up a crisis team

With all the conflicting sides on the equation—with one opposing the interest of the other—European Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines External Vice President Henry J. Schumacher said what is really needed to solve this problem is the setting up of a crisis team to handle the buyout.

“I propose that we create a crisis team composed of [the] government and the private sector to make tough decisions for the benefit of the tax-paying Filipinos, who deserve effective and functioning public transportation services,” he said.

The multisectoral team will be in charge of reviewing the implications of a buyout deal, and will determine how to effectively move forward to lessen all process of improving the system—with or without the takeover.

Subtly, Regidor, a research fellow at the University of the Philippines Diliman National Center for Transportation Studies, agreed, saying that the two camps should enter into a compromise for the benefit of the consumers.

“The only thing I can say about this is that [the] government and private sector should seek a compromise agreement or a middle ground. The government, though, is at an inferior position because it should— as representative of the public—work toward the public good,” he said. Should the two parties fail to arrive at a trade-off, the consumers are left to suffer the ill consequences of a government-private sector war. “By failing to arrive at a compromise agreement to resolve technical, including maintenance and financial issues, it appears that [the] government is the one at fault for the deficiencies of the MRT,” he said.

(To be continued)

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook